By Jordan Howes, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy

The long-planned highway expansion through the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest is once again moving forward, but without the level of environmental review, public input or scientific rigor that such a consequential project demands. Recent decisions by federal agencies regarding the Corridor H project between Wardensville, West Virginia, and the Virginia state line raise profound concerns about impacts to wildlife, public lands and cherished recreational resources.

Earlier this year, community groups and conservation organizations submitted detailed comments on the Supplemental Environmental Assessment (SEA) for Corridor H, urging federal agencies to require a Special Use Permit that would allow for meaningful public engagement. For months, agency records indicated that such a permit would be pursued. However, in November, the Federal Highway Administration issued a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) and announced that the Forest Service would instead rely on a Letter of Consent, effectively shutting the public out of further review. In response, advocates from the Virginia Wilderness Committee, Stewards of the Potomac Highlands, the Highlands Conservancy, and others submitted a comprehensive technical letter documenting new information and unresolved impacts that were not adequately addressed in the SEA or the FONSI.

At the heart of these concerns is the failure to properly assess impacts to sensitive and imperiled wildlife. The proposed highway would cut through habitat known to support the wood turtle, a species considered endangered by international conservation authorities and identified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in both West Virginia and Virginia. Despite extensive scientific literature documenting the wood turtle’s vulnerability to habitat fragmentation, road mortality, and population isolation, federal analyses contain no meaningful evaluation of how this project would affect local populations. Without basic population data, movement studies, or mortality estimates, agencies have concluded, without evidence, that the highway would not threaten the species’ viability in the forest. This is not informed decision-making; it is speculation at the expense of biodiversity.

Similar concerns apply to the federally endangered northern long-eared bat. Surveys have confirmed the presence of an active maternity colony within the project area, yet the Forest Service’s Biological Opinion concludes the project is “not likely to jeopardize” the species, even while acknowledging the permanent loss of hundreds of acres of roosting and foraging habitat and the likelihood that bats will be displaced, or killed—during construction. The assumption that bats will simply relocate and recover ignores the species’ ongoing range-wide decline and the cumulative impacts of habitat loss and fragmentation.

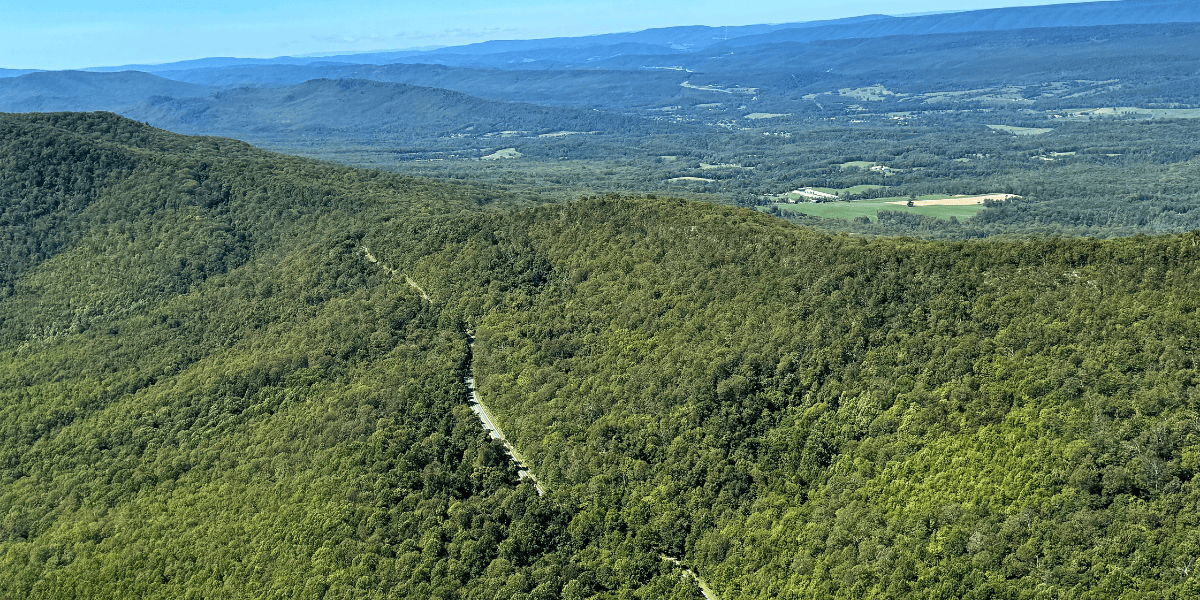

The project also threatens one of the region’s most important recreational resources: the Tuscarora Trail. This 250-mile long-distance trail, which connects to the Appalachian Trail and is part of the Great Eastern Trail network, crosses Route 55 at the crest of Great North Mountain. Thousands of volunteer hours have gone into maintaining this trail for hikers, equestrians, hunters and outdoor enthusiasts. Yet the SEA and FONSI largely dismiss long-standing safety concerns at this crossing and fail to recognize the trail as a significant recreation site protected under federal transportation law. Increased traffic volume and higher speeds would make an already dangerous crossing even more hazardous, with no meaningful mitigation proposed.

Beyond these site-specific issues, the broader problem remains the same: agencies are relying on outdated analyses rooted in a 1996 Environmental Impact Statement that no longer reflects current conditions, science, or public values. Over the past three decades, our understanding of wildlife conservation, forest management, and transportation impacts has evolved dramatically. So too has the importance of protecting intact public lands as climate change and development continue to fragment the landscape.

The National Environmental Policy Act, the National Forest Management Act and the Endangered Species Act all exist to ensure that decisions affecting public lands and wildlife are grounded in science, transparency and accountability. When agencies bypass thorough review and public involvement, they undermine not only environmental protections but public trust.

Although the FONSI has been issued, this process is far from over. The Forest Service is still determining the terms of its Letter of Consent, and continued advocacy is essential. Protecting wildlife, safeguarding public safety, and preserving the ecological and recreational integrity of our national forests are not optional considerations—they are legal obligations and moral responsibilities.

By placing this information into the administrative record, the technical letter that was submitted serves as both a warning and a roadmap: a warning about the irreversible harm that could result from uninformed decision-making and a roadmap for how agencies can still choose a more responsible path forward.