By Dr. Steven Krichbaum via Go North Alliance

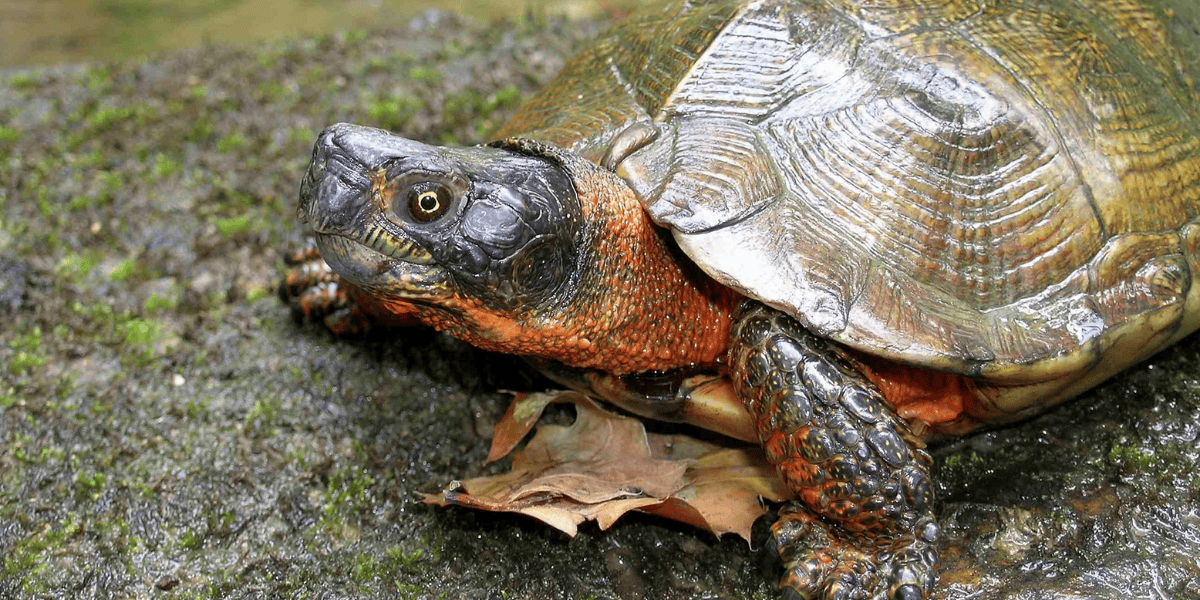

The red-legged jewel is one of North America’s most striking wildlife species: the Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta). The WT occurs from southeastern Canada and northeastern states of the USA down into northern Virginia and West Virginia. The Turtle finds refuge on private lands as well as various public spaces, such as the northern portions of the George Washington and Monongahela National Forests in WV and VA. Adult Turtles reach shell lengths of around 8 inches and weights of 1 kilo. They are renowned for their intelligence and can live to be over 60 years old.

They are amphibious omnivores who use a variety of aquatic and terrestrial habitats. After the Box Turtles and Tortoises (Desert, Gopher, Texas), Wood Turtles are North America’s most terrestrial turtle species. During the summer they disperse and are mostly terrestrial, living as do Box Turtles. In the spring and fall they stay closer to the streams and go back and forth between land and water. In winter they hibernate underwater in pools deep enough to not freeze entirely. Suitable Wood Turtle habitat is basically lower elevation forests with clear running low gradient waterways with rocky substrates [1 cite]. Studies clearly show that they may normally range up to 200-700 meters (660-2300 feet) from the water.

Because of the threats outlined below, the Wood Turtle (“WT”) is considered to be in some sense ‘imperiled’ in virtually every state in which it occurs. In fact, the Wood Turtle is designated as a “Species of Greatest Conservation Need” (SGCN) in the State Wildlife Action Plans of all 17 states in which they occur, including WV and VA, and is already considered to be “endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Wood Turtle is already absent from a significant part of its historic range. Only a restricted number of creeks and rivers in the Turtle’s range retain clear water, safe nesting sites, deep pools for overwintering, and associated undisturbed upland zones. There is much evidence of population extirpations or declines and a general range contraction/curtailment, with perhaps most of the extant populations/colonies of Wood Turtles being already very small with low densities [2].

Unfortunately, for over a decade the US Fish and Wildlife Service [“USFWS”] has been sitting on a petition from the Center for Biological Diversity [“CBD”] advocating the Turtle’s listing under the federal Endangered Species Act [“ESA”]. The good news is that with a Jan. 15, 2025 DC Circuit Court ruling in response to 2020 litigation, the CBD secured deadlines for the USFWS to finally decide whether the Wood Turtle and 75 other species warrant protection under the ESA.

The Wood Turtle, as do most turtle species, possesses life history traits that make populations especially vulnerable and sensitive to increased human-caused loss and mortality: slow growth, late maturity, long lives, low reproductive potential (small clutches), and high natural mortality of eggs and hatchlings (such as from predators like Raccoons) [3]. High adult survivorship and a great many reproduction events are generally necessary to maintain turtle population viability. Due to the demographic implications of these traits, turtle populations may not be able to sustain even modest additional adult take/mortality above natural attrition. With regard to population persistence, research shows that Wood Turtles may be the North American turtle species most sensitive to the loss of adults from a population [4]. The implications of this relevant factor are striking. It means that if enough adults are not protected from takings, then populations inevitably collapse. Increases in risks associated with terrestrial movements in areas of overlap with human activity, e.g. roads and traffic, are clearly at odds with the high adult survivorships required to maintain populations (Give Turtles a Brake) [5].

As a habitually amphibious animal, the Turtle is vulnerable to the degradation and destruction of both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Their populations are threatened by habitat loss/degradation/fragmentation, as well as by exploitation (poaching/collection for pets), various forms of pollution, climate change, emerging diseases, and direct mortality. Roads are part of the habitat destruction/degradation/fragmentation and direct mortality, as are logging, burning and drilling operations, agriculture, and commercial/agricultural/residential development. My research on VA/WV Wood Turtles showed they tended to avoid recently logged sites. Of course, aside from altering temperature and precipitation, climate change can alter the composition, structure, and functionality of the ecological communities in which the Turtle lives.

Timber cuts, roads, development, agriculture and other conversion of habitat result in the fabrication of ecological edges with a multitude of deleterious impacts to habitat quality/quantity. In many cases in the eastern USA, areas influenced by edge effects dominate the landscape [6]. For species such as the Wood Turtle, this condition exacerbates exposure to depredation. Predation pressure having devastating impacts upon nesting success and subsequent recruitment are reported throughout the Wood Turtle’s range. In some places predation pressure may be the single most important factor affecting the sustainability of Wood Turtle populations. Due to direct human subsidy (e.g., garbage), habitat alteration such as increases in ecotonal edges and roads, and extermination of large predators (e.g., Cougar and Gray Wolf), populations of many meso-predators such as Raccoons have markedly increased in the East (“mesopredator release” [7]). Even a small number of such creatures can have a devastating impact upon turtle populations. Predation pressure on nests and Turtles from booming medium-sized predatory mammal populations (such as Raccoons and Skunks) is especially raising havoc with Wood Turtle populations. Reported nest depredation is often high, e.g., 70-100% of nests in some places, and intact nests do not necessarily hatch out all the eggs [8]. I have observed Raccoons waiting closeby for a Wood Turtle to finish laying her eggs so then they can be dug-up and eaten. Nest predation is likely amplified by the fact that many Wood Turtles nest alongside roads. Such nesting sites that appear physically good but actually result in nesting failure are a form of what is termed an “ecological trap” [9].

And one must never forget that implementation of logging/ roading/ development projects does not just alter habitats in harmful ways (such as reductions in abundance or diversity of vital ground floor cover and food resources), it also irreparably results in incomprehensible amounts of direct mortality of wildlife — squashing and burning turtles and toads and snakes and salamanders and nestlings and snails and slugs and other invertebrates, all those small and slow creatures who cannot run away or fly away from harm, including those who live in trees; all of whom are significant components of forests. Now more than ever we need to be on the side of life and be kind, instead of expanding the blood bath into roadless areas and other lands.

Poaching/collection (“overutilization”) for commercial and recreational purposes are big threats. Wood Turtles fetch very high prices both domestically and overseas, which are huge incentives for illegal trade. The Wood Turtle featured prominently in high-profile busts of illegal wildlife sellers; for instance, a poacher was arrested in West Virginia with over 100 wild-caught Wood Turtles in his possession [10].

With pressures on the species mounting, sites on relatively undeveloped public lands grow increasingly crucial as refugia for the Turtle. Preserving Wood Turtle populations and habitat in our National Forests and other public lands appears critical for ensuring their long-term survival.

In addition to the physical on-the-ground threats are the underlying threats enacted by political and regulatory changes. Efforts are underway to alter the ESA by claiming that the destruction and degradation of habitat does not constitute “harm” to species. To those supporting this I ask — so if your home is burned to the ground or demolished with heavy equipment while you are not there, then you are not harmed, right ? And the CEQ regulations implementing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) on NFs have been shoved aside, thus preventing well-informed decision-making and meaningful public participation. And a proposal to rescind the Rule that protects roadless areas on NFs from logging and roading is underway. Plus, Trump has issued an Executive Order to massively increase logging on our National Forests.

Further, there is now a proposal to extend Corridor H through the GWNF in WV that is within the Wood Turtle’s range. I have seen roadkilled Wood Turtles on small roads passing through the GW in WV and VA. Such a 4-6 lane highway as Corridor H is precisely what the Turtles don’t need [5]. It needs to be stopped.

Because of all the past and present threats/harms to their viability, the Wood Turtle should be listed under the ESA. Within the Turtle’s range in the heavily populated NE part of the USA much of its natural habitat of clear-running streams and associated intact forest is undergoing/has undergone intense human population growth and development pressures. Throughout the Turtle’s range, entities such as the USFS, corporations, and individuals are implementing or proposing actions with the potential to harm Wood Turtles or their habitat directly, indirectly, and/or cumulatively.

Aside from the ecological/biological necessity of stopping the current ongoing harms/threats that result in habitat loss/degradation and direct killing or removal of Turtles from wild populations, a clear reason listing is needed is the : “Inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms” (one of the formal criteria for ESA listing). The Turtles certainly are not always adequately considered (if at all) in conservation and development planning. Designations with little legal weight, such as “Species of Greatest Conservation Need”, do not stop people from poaching them nor stop harmful projects from being implemented [11]. Wood Turtle population locations are not stringently protected from intensive logging, burning, road construction, or various motorized recreational activities. Past and current timber sales on top of Wood Turtle populations and habitat on the George Washington NF are a perfect example, such as the North Shenandoah Mountain logging/burning project in WV & VA.

In comments and formal Objections submitted to the Forest Service about projects on the GWNF I have asked repeatedly that they protect the Wood Turtle’s “core habitat” and not log, burn, and put roads in it. This, such as simply moving the cutting units, they have repeatedly refused to do. For Wood Turtles, the terrestrial zones that generally extend out to at least ca. 300 meters from both banks of waterways are their “core habitat” [12] where conservation efforts for this species can and must be focused. The 300m metric is consistent with numerous Wood Turtle studies throughout locations in the species’ range [13]. For example, in Maine, 95% of Turtle activity areas were within 304m of rivers and streams (Compton et al. 2002), while in VA/WV, 95% of Turtle points were within 295m (Krichbaum 2018). The 300m prescription should generally be considered a minimum as this zone may not include lengthy pre-nesting peregrinations by female Wood Turtles or connectivity to other populations. Improving or protecting the quality of other habitats outside of more strictly protected core areas can be crucial [14].

In short, we need to develop our understanding of the Turtles, not develop their habitat. Just as for multitudes of other species, for the Wood Turtle to have a good chance for a long-term future we must not only rigorously protect their core habitat, we must think BIG and think CONNECTED and protect some entire landscapes, especially on public lands [15]. A multitude of other flora and fauna, including human communities, will benefit when we accord Wood Turtles enhanced on-the-ground protections.

The contact person for Wood Turtle listing at the USFWS is Julie Thompson-Slacum at the Chesapeake Bay Ecological Services Field Office in Maryland: julie_thompson-slacum@fws.gov

Steven Krichbaum, PhD, a herpetologist and conservation biologist who lives in VA, has worked with grassroots groups for 35 years seeking protection of wildlife and public lands. He’s never met a turtle he didn’t like.

Citations

1. Ernst, C.H. and J.E. Lovich. 2009. “Wood Turtle”, pp. 250-262 in Turtles of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. 840 pp.

2. Jones, M.T. and L.L. Willey. 2015. Status and Conservation of Wood Turtles in the Northeastern United States. Final Report to the Regional Conservation Needs (RCN) Program. Accessible at http://rcngrants.org/sites/default/files/datasets/RCN2011-02v2.pdf

Willey. L.L. et al. 2022. Distribution models combined with standardized surveys reveal widespread habitat loss in a threatened turtle species [WT]. Biological Conservation Vol. 266 (Feb. 2022).

3. Gibbs, J.P. and G.D. Amato. 2000. “Genetics and Demography in Turtle Conservation”, pp. 207-217 in M.W. Klemens (ed.), Turtle Conservation. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. 334 pp.

4. Reed, R.N. and J.W. Gibbons. 2003. Conservation status of live U.S. non-marine turtles in domestic and international trade. Report to US Department of the Interior and US Fish and Wildlife Service. 92 pp. www.tiherp.org/docs/Library/Turtle_trade_report.pdf

5. Krichbaum, S. 2024. Give Turtles a Brake. https://www.counterpunch.org/2024/06/07/give-turtles-a-brake-3/

6. Fletcher, R.J., Jr. 2005. Multiple edge effects and their implications in fragmented landscapes. Journal of Animal Ecology 74: 342–352.

Harper, K.A. et al. 2005. Edge influence on forest structure and composition in fragmented landscapes. Conservation Biology 19: 768-782.

Riitters, K.H. et al. 2002. Fragmentation of continental United States forests. Ecosystems 5: 815– 822.

7. Prugh, L.R. et al. 2009. The rise of the mesopredator. BioScience 59(9): 779-791

Browne, C.L. and S.J. Hecnar. 2007. Species loss and shifting population structure of freshwater turtles despite habitat protection. Biological Conservation 138: 421–429.

Mitchell, J.C. and M.W. Klemens. 2000. “Primary and Secondary Effects of Habitat Alteration,” pp. 5-32 in M.W. Klemens (ed.), Turtle Conservation. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. 334 pp.

Mullin, D.I. et al. 2020. Predation and disease limit population recovery following 15 years of headstarting an endangered freshwater turtle [WT]. Biological Conservation 245 (2020)

8. Rutherford, J.L., J.S. Casper, and B. Graves. 2016. Factors affecting predation on Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) nests in the upper peninsula of Michigan. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 15(2): 181–186.

Walde, A. D. et al. 2007. Nesting ecology and hatching success of the wood turtle, Glyptemys insculpta, in Québec. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2: 49–60.

9. Robertson, B.A., J.S. Rehage, and A. Sih. 2013. Ecological novelty and the emergence of evolutionary traps. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 28: 552-561

10. Hollowell, G. 2011. Federal sting nets reptile trader with 108 North American Wood Turtles in West Virginia. Turtle and Tortoise Newsletter 15: 29-31.

11. Visconti, E. 2022. Development and poaching erasing years of work to protect Wood Turtles in Virginia. Virginia Mercury. https://virginiamercury.com/2022/05/23/development-and-poaching-erasing-years-of-work-to-protect-wood-turtles-in-virginia/

12. Congdon, J.D., O.M. Kinney, and R.D. Nagle. 2011. Spatial ecology and core-area protection of Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii). Canadian Journal of Zoology 89: 1098–1106.

Semlitsch, R.D. and J.B. Jensen. 2001. Core habitat, not buffer zone. National Wetlands Newsletter 23(4): 5-11.

Semlitsch, R.D. and J.R. Bodie. 2003. Biological criteria for buffer zones around wetlands and riparian habitats for amphibians and reptiles. Conservation Biology 17:1219–1228.

13. Arvisais, M., J.-C. Bourgeois, E. Levesque, C. Daigle, D. Masse, and J. Jutras. 2002. Home range and movements of a Wood Turtle (Clemmys insculpta) population at the northern limit of its range. Canadian Journal of Zoology 80: 402–408.

Compton, B.W., J.M. Rhymer, and M. McCollough. 2002. Habitat selection by Wood Turtles (Clemmys insculpta): An application of paired logistic regression. Ecology 83: 833-843.

Jones, M. 2009. “Spatial ecology, population structure, and conservation of the wood turtle, Glyptemys insculpta, in central New England”. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Accessible at http://scholarworks.umass.edu/openaccessdissertations/39

Kaufmann, J.H. 1992. Habitat use by wood turtles in central Pennsylvania. Journal of Herpetology 26(3): 315-321.

Krichbaum, S.P. 2018. “Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians”. PhD Dissertation, Ohio University, Athens. 519 pp. Access at http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=ohiou1523017722959154

Latham, S. R., A. P. K. Sirén, and L. R. Reitsma. 2023. Space use and resource selection of wood turtles (Glyptemys insculpta) in the northeastern part of its range. Canadian Journal of Zoology 101: 20-31.

14. Hansen, A.J. and R. DeFries. 2007. Ecological mechanisms linking protected areas to surrounding lands. Ecological Applications 17(4): 974-988.

Quesnelle, P.E. et al. 2013. Effects of habitat loss, habitat configuration and matrix composition on declining wetland species. Biological Conservation 160: 200-208.

15. Krichbaum, S. 2023. “A Vision for Proforestation: The Appalachian Ecosystem Protection Act”. pp. 18-20 at https://www.heartwood.org/heartbeat/HBeat-Fall-2023.pdf

Krichbaum, S. 2024. “Protection And Connection: Reasons for an Appalachian Ecosystem Protection Act”. pp. 16-27 at https://www.heartwood.org/heartbeat/HBeat-Spring-2024.pdf

Krichbaum, S. 2024. “Landscape Ecology and National Forest Mismanagement”. Access at https://www.counterpunch.org/2024/09/24/landscape-ecology-and-national-forest-mismanagement/