By John McFerrin, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy

There are a couple of issues concerning solar power that may arise during the 2026 legislative session: net metering and community solar. One—net metering—will likely not come up. The other—community solar—will likely arise but based upon its fate in the past, may not make much progress.

Net Metering

Although there are solar systems completely off the electrical grid, most systems remain connected to the grid and use net metering. The customers have a bi-directional meter which measures electricity flowing both ways. At night and during the bleak mid-winter, when homes use more electricity than their solar panels can produce, they buy electricity from the power grid just as everybody else does. During sunny days, when homes produce more electricity than they use, they sell the excess to the power company. Customers are only charged should their use be more than what their system produced. This entire process is called net metering.

Back in the old days—when so few people had solar power that nobody really cared—the Public Service Commission adopted a rule that said that the price of electricity would be the same no matter which way it was going. For every kilowatt the consumer sold the power company, it could buy a kilowatt at the same price.

Two years ago, when solar power had started to take off, First Energy proposed that it be allowed to charge customers the full retail price for what the consumers used. For what the company bought from customers, it would pay a dramatically lower wholesale price.

Last year, Appalachian Power made a similar proposal to the Public Service Commission.

Both proposals resulted in negotiated settlements. Both utilities pay less for electricity the customer produces than the full retail price, but more than they had proposed to the Public Service Commission.

The Legislature will probably decide to leave well enough alone. Unless some business, person, or group steps forward to make this a legislative issue, it will probably assume the Public Service Commission will take care of it, and it does not have to.

If the Legislature gets involved, all bets are off. It could pass a statute requiring that electricity sold by the customer have the same price as electricity bought by the customer. It could adopt some other rate.

Community Solar

Community solar allows entities with big roofs—a business, a parking garage, a church, a medical center—to install solar panels on those roofs and then sell the power that it does not use. For example, a business with a big roof and no shade trees anywhere nearby could cover that roof with solar panels. With such a big roof, it would produce more electricity than is needed. It could then sell the right to use the excess.

Community solar would not be restricted to existing roofs. It could be constructed as a free-standing entity. People could buy shares in the electricity produced by a free-standing community solar operation just as they would in one installed on an existing rooftop. If West Virginia allowed community solar, freestanding community solar operations would probably be more common than those on big roofs.

As a practical matter, any community solar operation could not sell electricity to consumers directly. In addition to the legal barriers, there would be the practical problem of having to string wires, etc., to deliver the electricity. Instead, the excess electricity produced would go back into the electrical grid. Consumers would buy shares of the excess electricity produced by the business, the church, etc. They would then be credited on their electric bills in proportion to the shares they owned in the community solar operation.

This opens the possibility for all manner of people to have solar power who cannot have it now. Even though renters do not own their roofs where they could install their own solar panels, they could buy shares of the electricity produced from some big building or freestanding entity. Those who lived in shady spots where solar panels are not possible could buy shares. Those who could not afford the up-front investment in solar panels could buy shares.

It also opens the possibility of savings for consumers. Estimates are that consumers could save about ten percent on their electric bills by enrolling in community solar.

Even if this sounds like a good idea, it cannot happen in West Virginia under existing law. In West Virginia, electricity is sold by regulated monopolies (Appalachian Power and First Energy). They are regulated by the Public Service Commission, which sets rates and controls most aspects of their operations. As regulated monopolies, they control the poles, wires, etc. that a community solar operation would need to distribute electricity to its members.

This is where the Legislature comes in. Before community solar can become a reality in West Virginia, the Legislature would have to change the law. It would have to authorize community solar and require the Public Service Commission to adopt rules setting out how the monopolies it regulates (Appalachian Power and First Energy) would have to cooperate with community solar operations.

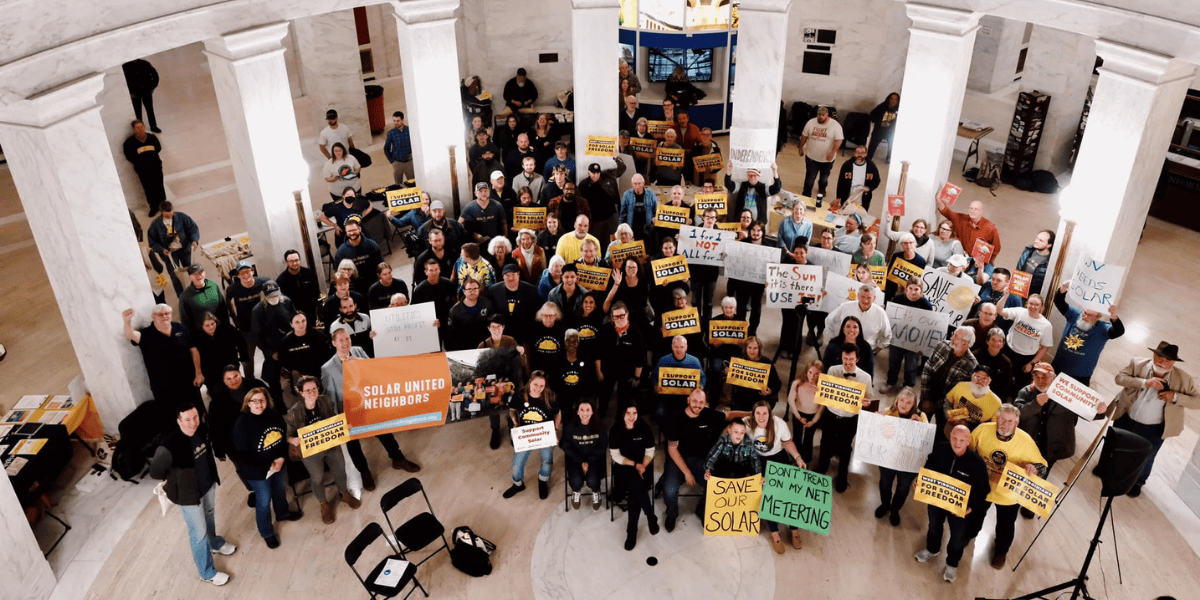

Bills to authorize community solar were introduced during the 2022, 2023, 2024, and 2025 sessions of the West Virginia Legislature. They did not pass. There will almost certainly be a similar bill introduced in 2026.

Community solar might meet the same fate in 2026. The dissatisfaction with rising utility bills might give it a boost, although the West Virginia Legislature’s automatic reflex that what is good for coal is good for West Virginia might kick in to defeat it.