By Jordan Howes, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy

Despite public outcry, state issues air quality permits for two off-grid power plants tied to world’s largest ammonia project

A proposal to build a sprawling energy and data hub in southern West Virginia is stirring deep concerns among residents, who say they’ve been left in the dark about the project’s health, environmental, and economic impacts.

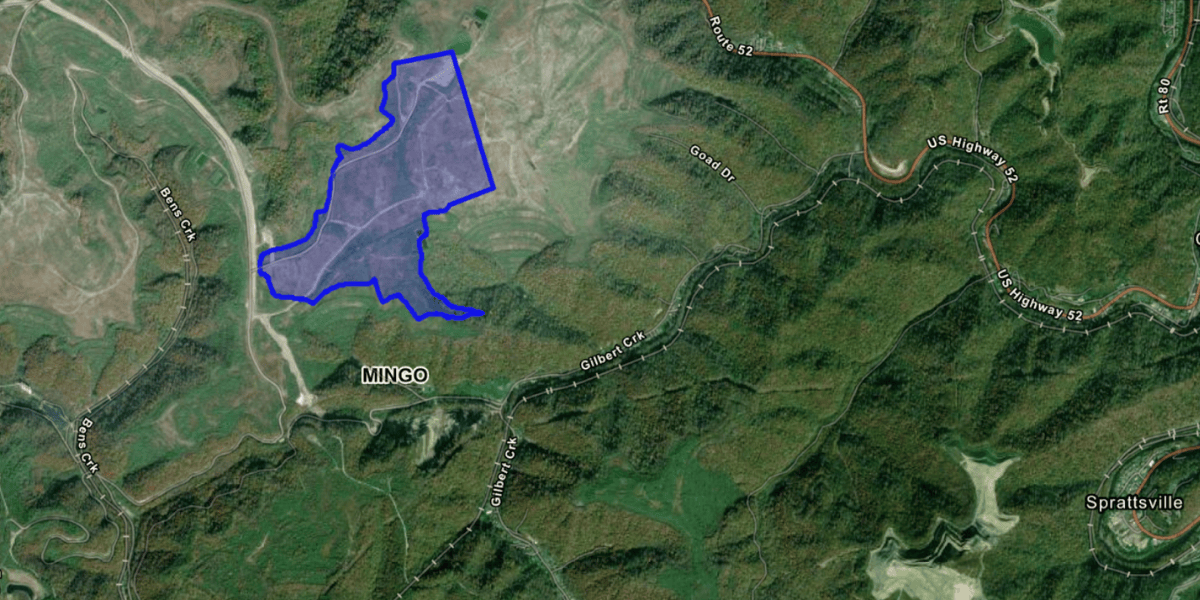

In April, TransGas Development Systems, a New York-based company, filed applications with the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to construct two off-grid natural gas–fired power plants and associated data centers — one on the former Twisted Gun Golf Course in Wharncliffe, the other at the Harless Industrial Park near the Mingo-Logan county line. Together, the facilities would be tied to the company’s larger Adams Fork Energy project, an ammonia production plant that, if built, would become the largest of its kind in the world.

At full capacity, the power plants would each operate 117 gas engines and could generate more than 2,400 megawatts of power — making them the third- and fourth-largest energy facilities in the state, behind only the John Amos and Harrison power stations. Each would also have the capacity to emit hundreds of tons of air pollutants annually, including nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, and fine particulate matter.

Concerns over secrecy and health impacts

Dozens of residents from Mingo and Logan counties gathered last month in Wharncliffe Park for an informal meeting led by organizers from the West Virginia Citizen Action Group (WV CAG). Participants voiced frustration over what they see as a deliberate lack of transparency. Critical details in the DEP’s air quality permits have been redacted, with officials citing “proprietary information.”

That uncertainty has fueled alarm in a region already struggling with high rates of black lung, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and other respiratory illnesses. Nearly every person in attendance said they knew someone with black lung disease.

Water usage is another flashpoint. According to project documents, TransGas intends to draw unlimited amounts of water from underground mine pools beneath the golf course to cool equipment and run operations. Residents, many of whom have endured years of unreliable water service and contamination, worry that corporate access to underground water resources will further disadvantage their communities.

Beyond the environmental questions, locals are skeptical about the promised economic benefits. While TransGas has touted 5,000 temporary construction jobs and 300 permanent roles, critics note that the company has announced major projects in Mingo County three times over the last 17 years — without completing any of them.

State issues permits despite public opposition

After weeks of public outcry and two hearings in August and September, the DEP’s Division of Air Quality (DAQ) has moved forward with the project. On October 2, 2025, the DAQ officially issued air permits R13-3714 and R13-3715, authorizing TransGas to construct and operate the two proposed off-grid natural gas power plants in Mingo County.

According to the agency, both facilities “will meet all applicable state and federal air quality rules and regulations” as outlined in the approved permit applications. The decision followed a 30-day public comment period, during which dozens of residents and environmental advocates voiced concerns about air pollution, transparency, and the project’s cumulative impacts on nearby communities.

The final permitting documents will soon be available on the DEP website, and printed copies can be requested by contacting Stephanie Mink at the DEP’s Charleston office.

Residents who participated in the comment process — or anyone whose interests may be affected — still have the option to appeal the permits to the West Virginia Air Quality Board under state law.

Calls for transparency grow across the state

The tension in Mingo County mirrors growing unease in other parts of West Virginia where large-scale industrial and data center projects have been announced with limited public input. In Mason County, residents recently gathered at the Point Pleasant River Museum seeking information about a separate proposal from Fidelis New Energy that would include a hydrogen plant, carbon storage site, and data center complex. Like the Mingo County project, residents there said they left the meeting with more questions than answers.

As readers of The Highlands Voice know, similar concerns have surfaced in Tucker County, where an off-grid power plant and data center complex proposed between Davis and Thomas caught the public off guard after redacted permit filings appeared in the local paper. The West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and local community groups have also called for greater transparency and local control.

Adding to residents’ frustrations, a recently enacted state law HB 2014 — supported by the governor — restricts local governments from regulating the noise, lighting, or land-use impacts of such facilities, effectively reducing communities’ ability to protect their quality of life.

The bigger picture

The Adams Fork project represents more than just a local development dispute. Across Appalachia, communities are grappling with new natural gas–based industrial projects promoted as economic lifelines, despite evidence of uncertain markets and serious environmental risks.

As state regulators clear the way for TransGas to proceed, residents say they will continue to demand transparency, independent oversight, and honest answers about how the project will affect their water, air, and daily lives.

Opponents argue that southern West Virginia deserves investment in industries that don’t require residents to sacrifice their health or environment for short-term economic promises.