By Hugh Rogers

Seen from Snowy Point, Canaan Valley’s northern half is a wetland mosaic unbroken by human landmarks. Turn around, and they appear in every direction. To the northeast, the giant Mt. Storm power plant reaches up in tall plumes from its stacks and reaches out in cables strung east, west and south. Farther north, another stack rises beside a coal preparation plant. To the southeast, highwalls bound the Stony River Reservoir. Nearby are grassy “reclaimed” strip mines. Along the western horizon, forty-four wind turbines palisade Backbone Mountain. (The Highlands Voice, November 2002).

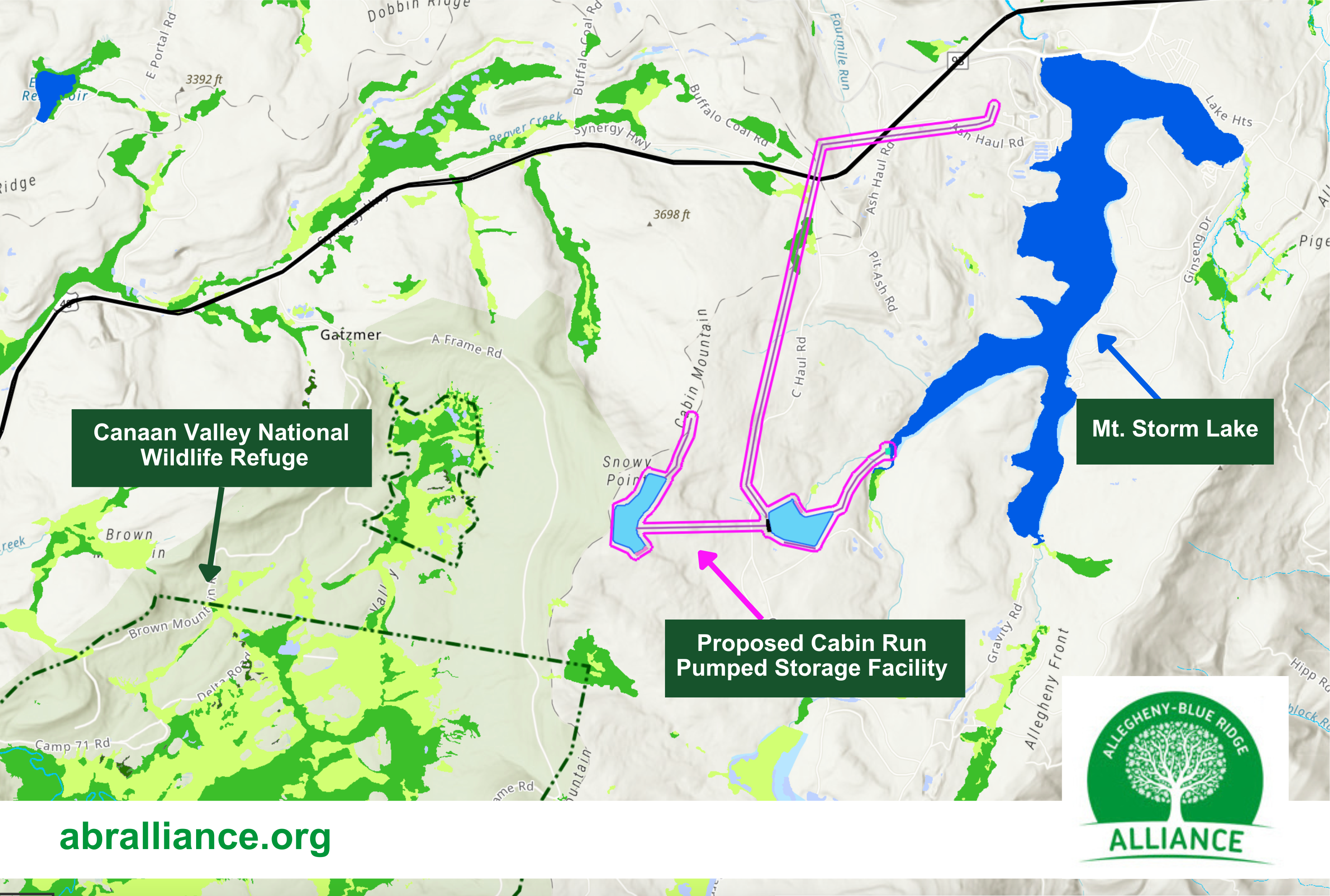

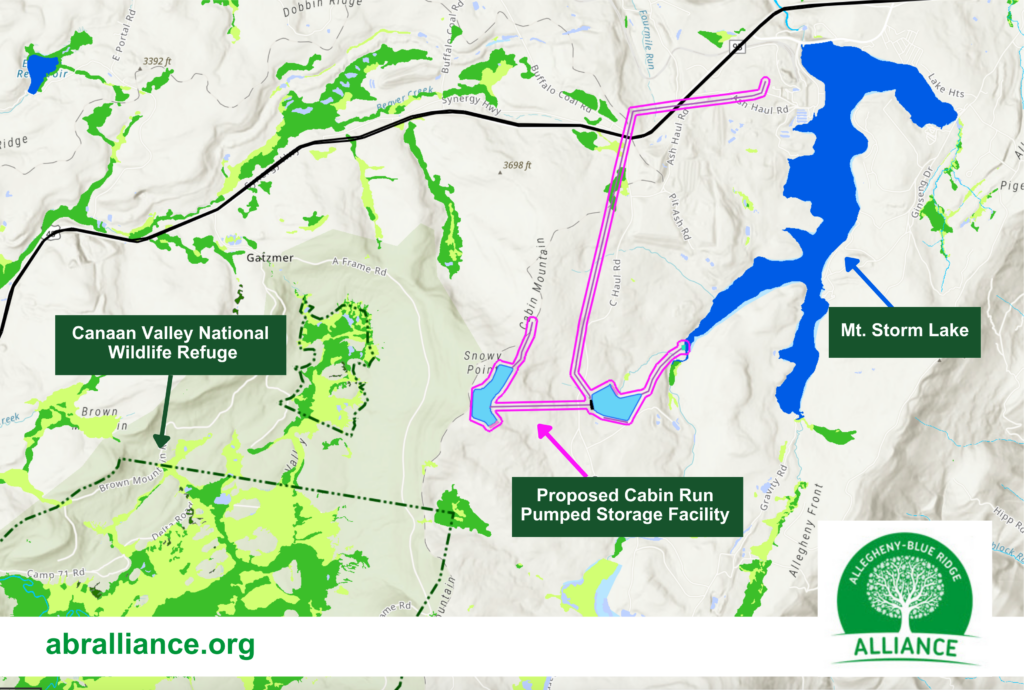

Snowy Point remains a Zen garden of white sand and rock islands at the tip of Cabin Mountain, ten miles north of Dolly Sods. Added to its view since 2002 are a hundred and thirty-two wind turbines strung along twelve miles of the Allegheny Front. They were planned when I wrote. What’s proposed today, directly below the Point, is an entirely different project.

This is the third attempt in five years to bring hydropower to the highlands.

The first, the Big Run Pumped Storage Hydro Project, would have placed a 1,200-acre impoundment on Backbone Mountain very near the proposed alignment of Corridor H. Both projects have encountered the same difficulty: avoiding the watersheds of Big Run Bog on one side and Tier 3 protected streams on the other. Big Run Bog is a National Natural Landmark containing many rare species of plants and animals. As such, it is protected by the National Park Service as well as the landowner, the Monongahela National Forest.

Speaking for the Park Service, the Department of Interior wrote, “the proposed Project will use more electricity than it generates, will eliminate more than 1,500 acres of carbon-sequestering forest, and [the lower reservoir] will dam and flood the valleys of at least four Cheat River tributaries.” To the claim that the Project could be built without damage to the environment, the department recited impacts to fish and wildlife, migratory birds, and threatened and endangered species, in addition to Big Run Bog.

For its part, the Forest Service refused to grant a special use permit for core drilling and other preliminary studies, saying the project could not be made compatible with the Forest’s management plan. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) then denied the application for a preliminary permit.

In its reply to critical comments filed by the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and other organizations, the applicant, FreedomWorks, maintained that it had considered numerous potential sites in West Virginia, and only Big Run was suitable. As if to prove that point, it submitted a second proposal, titled Ulysses Pumped Storage Hydro, that was so misplaced it had to be redesigned within a couple of months.

Its upper reservoir occupied the entire watershed of Mill Run, a tributary of Stony River below the Mt. Storm power station in Grant County. This proposal affected private landowners, and they were enraged. A local church that would have been taken became a meeting place for the resistance.

The lower reservoir, seven miles distant, would have flooded Falls Gap just downstream from Greenland Gap, an area of natural, scenic, and historic interest. It, too, is in private ownership but includes a Nature Conservancy preserve.

The Department of Natural Resources filed comments right away: the project likely would eliminate the trout fishery in two affected streams, could impact numerous rare species, and would be constructed in an area that contains known caves. The Highlands Conservancy sought more information and meanwhile asked to participate in the proceedings as an intervenor.

A question was raised among board members whether our opposition had become automatic. The majority considered skepticism to be justified in this case, given the obvious problems with the Tucker County proposal and the flawed design of the second one. Moreover, both county commissions had seemed willing to give their go-ahead based on little more than the magic word, “jobs”. Due diligence had to come from private associations.

As it happened, the Ulysses project was defeated by overwhelming public opposition. A straw poll of landowners showed practically all would refuse to sell to the developer. Without the possibility of using eminent domain, Freedom Works was blocked. Shortly afterward, it withdrew the preliminary permit from FERC.

In his report on ill-fated Ulysses in the Voice (April 2020), David Johnston neatly summarized the pros and cons such proposals would face going forward.

Pro: “the potential to replace fossil fuel-generated peak demand electricity with energy generated by renewables.”

Con: “their large reservoirs . . . unavoidably will have large impacts on environmental, scenic, and recreational values, and on the people with ties to the affected land.”

Now comes the Cabin Run Pumped Storage Project. Its proposed site is owned neither by the public nor private individuals; it’s the property of Laurel Run Mining. Presumably, that corporation supports the project.

Also, unlike the previous proposals, this one does not require large reservoirs. Everything about it is compact. The surface area of the upper and lower reservoirs is 60 acres, one-twentieth as large as Big Run’s or Ulysses’. The vertical drop is just 500 feet, less than half as much as theirs, and the penstock runs less than a mile. It’s close to existing transmission lines. Annual output is estimated at 671,000 megawatt-hours, roughly a sixth as much as Big Run.

A lot we don’t know and can’t predict may come to light during the FERC process. How would construction affect the geology and chemistry of previously mined areas? How would “fill or refill” of the reservoirs affect Mount Storm Lake? Stay tuned.

Although the project is located on Cabin Mountain, “Cabin Run” doesn’t appear on any map. The tributary affected by the project is Red Sea Run. Perhaps the applicant wished not to be thought of as a Moses parting its waters into reservoirs.

Note: Readers may recall the proposal to flood much of Canaan Valley for the Davis Power Project. That was the first attempt to bring hydro to the highlands (and the Highlands Conservancy played a major role in its defeat). But that was fifty years ago, before many government inducements for renewable energy.