By James M. Van Nostrand, Charles M. Love, Jr. Endowed Professor

Director, Center for Energy & Sustainable Development

West Virginia University College of Law

One of the most powerful and yet relatively unknown agencies in West Virginia is the Public Service Commission (PSC). The PSC is charged with regulating the rates and practices of all the investor-owned utilities in the state which, in addition to electricity and natural gas, include telecommunications, water and sewer. The PSC is composed of three commissioners, appointed by the Governor and subject to confirmation by the state senate. Commissioners serve six-year terms and, by statute, no more than two commissioners can be from the same political party.

The PSC is an independent agency, in that the commissioners have fixed terms, and can be removed before the end of their terms only for incompetency, neglect of duty, gross immorality or malfeasance. The six-year terms are “staggered,” such that every two years, one of the three commissioners’ terms will expire. Thus the ability of the Governor to implement sweeping changes at the agency is very limited; the Governor has the authority to appoint one of the three commissioners to serve as chairman, to serve at the Governor’s “will and pleasure,” but can appoint new commissioners to the agency only upon expiration of an existing commissioner’s term. The chairman serves as the chief administrative officer of the agency.

The current chairman of the PSC is Charlotte Lane, a longtime energy industry lawyer-lobbyist and former state legislator. Bill Raney, the former president of the West Virginia Coal Association, joined the PSC in August 2021. The third, and relatively silent commissioner is Renee Larrick, a former teacher and business manager for a law firm. All three of the commissioners were appointed by Governor Jim Justice.

The West Virginia PSC is charged with setting “just and reasonable” rates, which is a very broad grant of authority. It gives the PSC considerable discretion in deciding what level of utility rates are “reasonable” and, in turn, empowers the PSC with considerable oversight authority over the utilities it regulates and the practices and policies followed by the utilities in providing utility service. The wide range of decisions by utility management overseen by the PSC includes the process for selecting the particular generating resources (coal, natural gas, or renewable resources) acquired by utilities to serve their customers, which involves integrated resource planning. The PSC’s broad grant of authority also comes into play in whether utilities will be required to offer their customers a range of energy efficiency programs (such as rebates for weatherization, HVAC equipment and Energy Star appliances) to help them manage their energy costs.

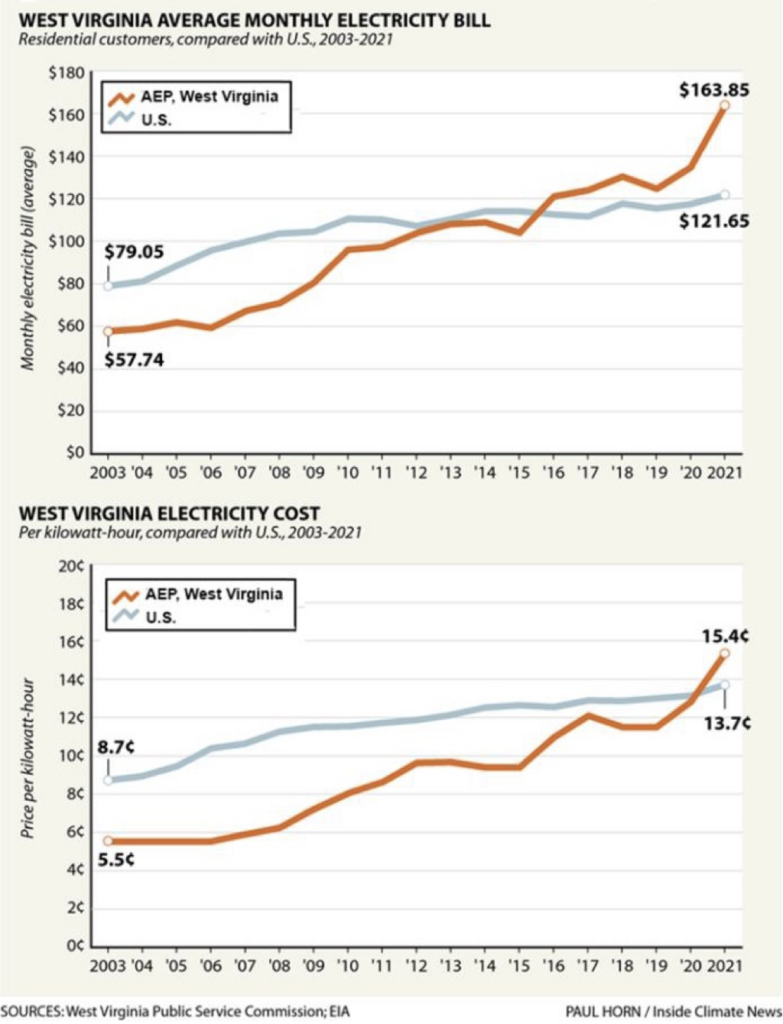

For the past dozen or so years, the PSC has failed miserably in its obligation to protect the interests of utility ratepayers. Rather, its decisions have uniformly favored the coal industry, and the utilities that burn coal to generate electricity. In 2008, West Virginia had the lowest average electricity rate in the country; by 2022, 17 other states had lower residential rates. Due to the pro-coal decisions made by the PSC since 2008, electricity prices in West Virginia increased at a rate that was five times the national average between 2008 and 2020. Figure 1 below, from a recent article in Inside Climate News, compares electricity prices and monthly bills for customers of American Electric Power (AEP) with the U.S. average since 2003. AEP is the parent company of Appalachian Power and Wheeling Power in West Virginia.

How did we get here? It started with decisions by the PSC in 2013 and 2014 to allow electric utilities to transfer old, uneconomic coal plants from their unregulated, competitive subsidiaries, to the regulated rate base, where the losses from continued operation would be borne by West Virginia ratepayers rather than utility shareholders. In 2013, the PSC authorized Mon Power and Potomac Edison to acquire 80% of the Harrison plant, followed in the same year by Appalachian Power acquiring the Amos coal plant and, in 2014, Wheeling Power acquiring 50% of the Mitchell coal plant.

In the face of nationwide trends to move rapidly away from coal towards cheaper and cleaner natural gas, we doubled down on coal in West Virginia. As of 2021, 91% of the electricity produced in West Virginia was fueled by coal. Meanwhile, the percentage of electricity generated from coal nationally declined from 48% in 2008 to a projected 19% share in 2023.

Compounding the continuing commitment to an uneconomic means of generating electricity (coal), the PSC refuses to do the one thing that would help ratepayers cope with their soaring electricity bills: requiring utilities to offer energy efficiency programs. Data from the Energy Information Administration shows West Virginia utilities spent about three dollars per customer in 2021 on energy efficiency, compared to a national average of $36. Our energy efficiency policies rank 48th among the 50 states, according to the Annual State Scorecard published by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. As a result of this failure to provide ratepayers with the means of managing their energy costs, monthly bills have risen even more sharply than the increase in rates, because per capita energy consumption in West Virginia is 20% above the national average.

It has only gotten worse in the past 15 months. In August 2021, the PSC authorized AEP to spend $383.5 million for environmental upgrades at its three West Virginia coal plants. The expenditures are necessary to keep the Mitchell, Amos and Mountaineer coal plants open past 2028. The PSC completely disregarded AEP’s testimony in the case that showed the ratepayers of Wheeling Power — which owns the Mitchell plant — would be better off, by $27 million per year after 2028, if the plant were retired, because of the availability of cheaper resources on the market.

Two months later, the price tag grew to $448.3 million when regulators in Virginia and Kentucky said “no” to recovery of their states’ share of the environmental upgrade costs. AEP simply refiled its case at the PSC to stick West Virginians with the costs avoided by Virginia and Kentucky. And, of course, the West Virginia PSC approved the higher amount in a decision issued in October 2021.

Just to make it perfectly clear that the PSC wants these plants to keep operating — regardless of whether cheaper sources of energy might become available — the PSC’s October order further directed AEP to spend whatever money it takes to keep the plants open to at least 2040 (even though AEP never formally requested approval for any expenditures after 2028).The continued investments in these uneconomic coal plants will lead to massive rate increases for AEP ratepayers in the future, given the growing inability of coal plants to compete in the wholesale energy markets in the face of cheaper alternatives, such as natural gas, wind and solar.

But the PSC has a solution for that as well, and it gets even worse for West Virginians: require the utilities to keep operating the coal plants at historical levels, even if cheaper sources of electricity are available. In hearings in late 2021 involving AEP’s and FirstEnergy’s annual power-cost adjustment filings, the PSC challenged the utilities’ decisions to operate their systems in a manner that produces the lowest costs for customers (which, frankly, is what utilities are obligated to do). The utilities’ strategy to operate economically has resulted in coal plants running less often (measured by the “capacity factor,” or a plant’s actual output compared to its maximum output). Utilities were acting prudently to displace coal-fired generation with lower-cost energy supplies available from purchases in the wholesale market (in our region, the PJM Interconnection), as well as power purchase agreements with wind and solar projects. AEP’s 2021 filing, for example, showed capacity factors of 34.7%, 49.6% and 57.3% for the Mitchell, Amos and Mountaineer plants, respectively. This was unacceptable to the coal-friendly PSC.

The PSC indicated in its decisions last fall that it expects capacity factors “in the mid- to high 70% range.” What does this mean for West Virginians’ electricity bills? Further massive increases in utility rates, as the PSC stubbornly refuses to allow electric utilities to join the clean energy revolution that has produced dramatic reductions in wholesale electricity prices across the country.

The narrative of “what’s good for the coal industry is good for West Virginia,” has certainly guided the PSC’s decisions since 2008 and, probably more than any other example, the results proved the cruel falsehood of the guiding principle. Allowing the utilities to continue to be over 90% dependent on one fuel source without diversifying into cheaper, cleaner sources of energy – including energy efficiency – might have been good for the coal industry, but it is clear that notwithstanding the PSC’s futile efforts to do so, the coal industry cannot and should not be bailed out on the backs of the West Virginia electric ratepayers. They simply cannot afford it, and never have been able to.

I spent the last chapter in my book, The Coal Trap: How West Virginia Was Left Behind in the Green Revolution, identifying some of the policies that should be given serious consideration as the state moves forward in the third decade of the 21st century. One section of that chapter focuses on regulatory reform at the PSC, which is long overdue and has proven to be urgently needed given the developments over the past 15 months. It’s essential that this powerful state agency start implementing policies that will position West Virginia’s electric utilities to provide the clean energy resources demanded by the markets of the 21st century.