By Olivia Miller, Program Director, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy

West Virginians are being asked once again to sacrifice their farmland, their mountains, and their pocketbooks—all to keep the lights on for Virginia’s ever-expanding data center corridor.

The proposed Mid-Atlantic Resiliency Link (MARL), a 155-mile high-voltage transmission line planned by NextEra Energy, would stretch from Greene County, Pennsylvania, through Monongalia, Preston, Hampshire, and Mineral counties in West Virginia before terminating in Loudoun County, Virginia—also known as Data Center Alley. The line is designed to deliver roughly 750 megawatts of power to fuel Virginia’s rapidly growing digital infrastructure.

That electricity will come directly from West Virginia’s coal-fired power plants—including Fort Martin, Harrison, Mitchell and Longview—meaning our state’s fossil-fuel generation will be used to power Virginia’s data centers, not West Virginia’s own communities.

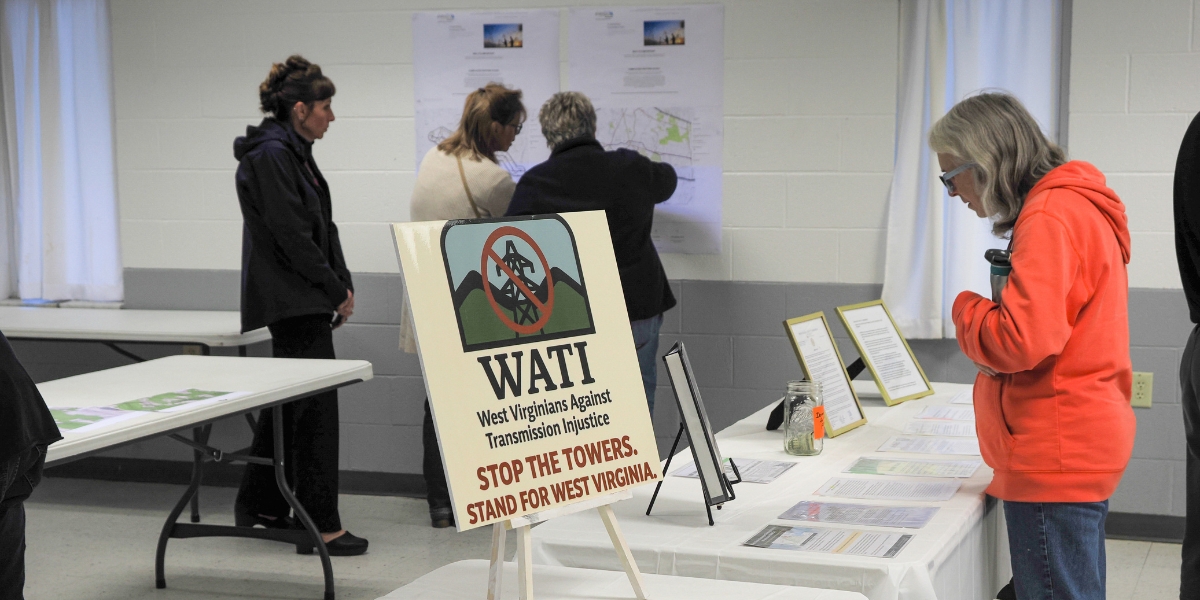

But as several speakers made clear at an Oct. 15 community meeting hosted by West Virginians Against Transmission Injustice (WATI) at the Cheat Lake Fire Hall, the power isn’t the only thing being exported—so are the costs, the impacts, and the risks.

Delegate Dave MacCormick, who represents the Cheat Lake area, didn’t mince words: “This power line increases our costs, doesn’t do anything to benefit us. Essentially, we’re being an extension cord to Virginia.” He said he’s already delivered letters of opposition to Governor Patrick Morrisey and the West Virginia Public Service Commission (PSC), which will ultimately decide whether the project moves forward.

The PSC—three appointed individuals in Charleston—could greenlight the project as soon as this fall. Local officials across the region, including members of the Monongalia County Commission, have expressed their opposition. “We see no tangible benefit to the state of West Virginia,” one commissioner said. “Name your county—there’s nothing here that does anything benefit to us.”

For landowners like Kent Hunter, whose property sits near University High School, and Beth Ann Bossio, who operates a seed and Christmas tree farm near the proposed route, the project threatens not just scenery but livelihoods. “It is a land grab,” Bossio told the packed room. “Every day it’s weighing on all of our minds.”

Despite promises of “local benefits,” WATI members and speakers pointed out that the math doesn’t add up. Counties may receive property tax revenues, but those funds are assessed by the state and depreciate each year—meaning the payout dwindles quickly. And since utilities are allowed to recover their costs through customer rates, West Virginians will ultimately pay for the very project being built across their land.

“They’ll provide that money by raising our rates and giving some back to the county,” one attendee said. “They don’t actually pay taxes—it’s coming out of our pockets.”

Meanwhile, the real beneficiaries—Virginia’s data centers and the multinational corporations behind them—will continue to demand more power. PJM Interconnection, the regional grid operator, has already identified an additional 750-megawatt shortfall due to data center growth and is considering a second MARL line, possibly connecting to a new natural gas-fired plant in West Virginia.

In other words, the energy flowing from our coal plants will keep servers humming in Northern Virginia, while West Virginians are left to bear the environmental, economic, and social costs of extraction.

Virginia reaps the digital profits; West Virginia shoulders the extraction, infrastructure, and environmental sacrifice.

Adding to these concerns is another proposal known as the Valley Link Project—a sprawling 260-mile network of new 765-kilovolt transmission lines proposed by Transource Energy that would cut across Barbour, Braxton, Calhoun, Grant, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, Kanawha, Lewis, Preston, Putnam, Roane, Tucker, and Upshur counties. Like MARL, the Valley Link lines are part of PJM’s regional transmission expansion plan, designed to move massive amounts of electricity eastward to serve Virginia’s energy-hungry data centers. Together, the MARL and Valley Link projects represent an unprecedented buildout of industrial-scale transmission across the Mountain State—exporting West Virginia’s coal and natural gas power to keep Virginia’s data center industry online.

West Virginians Against Transmission Injustice (WATI) formed earlier this year as a grassroots response to the MARL proposal, bringing together residents, farmers, and local officials across north-central West Virginia. The group aims to educate communities, help landowners intervene in PSC proceedings, and hold both NextEra and state officials accountable.

“Even if you don’t have the transmission line in your backyard or in your view,” said Hunter, “it’s going to impact each and every one of us in West Virginia.”

WATI urges residents to stay engaged, contact their legislators, and prepare to intervene when NextEra files its permit with the PSC—likely this fall. Landowners who intervene gain legal standing to testify, file briefs, and appeal PSC decisions. Those who don’t risk being left out entirely.

For longtime energy-justice advocates like Keryn Newman, who helped stop the PATH transmission project more than a decade ago, the fight feels familiar. “We’ve seen this before,” she said. “They promise economic benefit and reliability, but what we end up with is higher rates, lost farms, and irreversible scars on the landscape.”

As data centers multiply across the Mid-Atlantic, their energy footprint is sprawling outward—crossing borders and burdening communities that will never see the supposed rewards.

West Virginians, once again, are being asked to pay the price for someone else’s power.

For more information or to get involved, visit wvatli.org.